Wherever I travel across the British Isles, there is always something new to see. New landscapes, new creatures, new people; Britain holds an abundance of treasures — some large enough to leave you speechless, others small enough to require a magnifying glass to enjoy them.

In recent times, something else — something old — has enlivened each trip I take to a new location, offering me something different to explore. Parish churches. Whereas a few years ago, I would have hurried past these old buildings to get promptly to the nearest nature reserve, I now take a detour off the beaten path to seek out the wonders, mysteries, and beauty that our parish churches offer to the one who takes the time to seek and marvel.

Much is still unknown and undecipherable to me as I try and “read” the various architectural styles, masonry, and furnishings of all these diverse church buildings. It will take much time and practice for me to learn this new visual language. However, if the door to the church can be opened, there is something that is clearly and abundantly legible — that is if the church still has them.

If one is fortunate, the old wooden pews lining the nave will hold numerous, colourfully embroidered rectangular cushions; each one unique in its depiction of local parish life or decorated with various archaic looking patterns. These are church kneelers, used for kneeling during prayer — and I have become fascinated by them, not only for their diversity and quaint folk-styles, but also for the stories they tell of their place. Coming across a church full of kneelers is like walking into an old secondhand bookshop— you never quite know what subjects will be on display. Some subjects will be odd, some will be familiar; some will be old, some will be modern, but all will tell a local story.

Church kneelers an important part of our cultural history as a nation and are one of the best examples of folk art. Indeed, they are ‘localist art’ par excellence. A wealth of information about the local area can be gleaned from the kneelers — what the prevailing industry and economy is; what has happened in the place’s history; what animals and plants are common and what ones are special; and most of all, what are the local people proud of and want to display. All these and more, will be the chosen subjects depicted on the kneelers, painstakingly embroidered by local women, and sometimes men.

Though kneelers are possibly the most abundant form of folk art in Britain and certainly among the richest and most diverse, the art form is under threat. Every year, pews are ripped out of parish churches to make the buildings more “accessible” and modern — and out with the pews go the kneelers. Many end up in landfill. Precious pieces of local art condemned to the processes of decay and degradation among heaps and heaps of modernity’s trash. This is not ok. This is a national tragedy, but one very few know is going on apace.

As one authority on kneelers has noted “In a hundred years’ time, people will be fascinated by the social history illustrated on kneelers. A thatcher’s tools, a sewing machine, an oil rig will seem strange and wonderful. How many of the birds and plants featured will still be common?”1 We cannot lose this valuable and beautiful record that future generations will enjoy and use to learn about our own times and our own cherished places.

If you are a member of a parish church, please advocate on behalf of your kneelers. Let them not become the latest victims of modernisation and convenience. For the rest of us, there is something we can do — we can document the kneelers that we find on our journeys. The website Parish Kneelers is run by volunteers and is devoted to creating an archive of these valuable pieces of folk art in perpetuity. Whenever we visit a parish church, we can look out for its kneelers and take a few minutes to document and archive what we find. Such an endeavour helps to preserve a part of what makes Britain special.

And now on to some examples of kneelers…

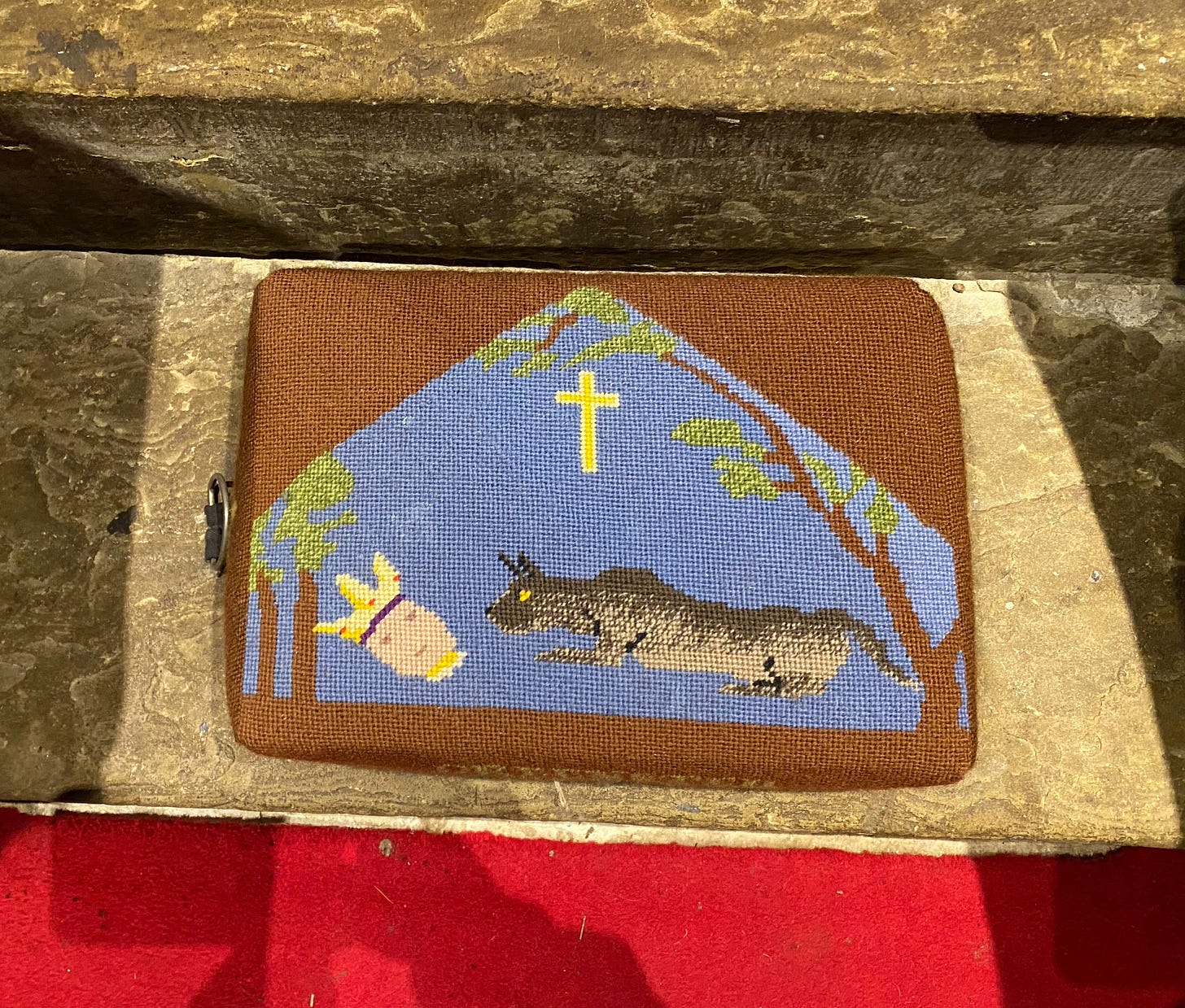

Below are some of the kneelers from two different churches at opposite ends of England. See what you can decipher about the local area from the subjects on display.

St John The Evangelist, Cowgill, Cumbria

Agricultural images dominate the designs — which is to be expected as the church is in a very isolated rural location. But what kind of agriculture? Though there is one kneeler with a sheaf of wheat, it is outnumbered by images of pastoral scenes: sheep, cows, and sheepdogs. This suggests we are in a marginal landscape suited to livestock and not crops. That is correct. We are in the heart of the Yorkshire Dales, a land of upland fells and limestone plateaus where Swaledale and Rough Fell sheep nibble the grass amongst fields bounded by picturesque dry stone walls. We are also in Red Squirrel country, this being a stronghold for this rare and beautiful creature who has been replaced by the invasive Grey Squirrel across much of the rest of the country.

All this local knowledge can be gleaned from the kneelers — they are a reflection of the distinctives of the place and what its residents cherish and want to showcase.

St Andrews, Greensted, Essex

Greensted church is my favourite church building in the whole of the country. Entering through its old oak doors is like stepping into a fairytale cottage that could be deep in the darkest wood. I have written about it before, describing in detail the unique treasures that can be found there, but I could have just shown you these kneelers as they tell the story of Greensted better than I could.

In contrast to Cowgill, Greensted is in the lowlands of Britain, in amongst fields lined by hedgerows and ditches. The land is very flat and fertile making it perfect for arable farming: mostly wheat and oil seed rape. Lo and behold, the kneelers capture this agricultural context as shown by the tractor which is ploughing the arable fields in preparation for sowing. The other kneeler of note in this regard to local geography is the one with oak leaves and acorns. Oak woodlands are dominant here in Essex and the oak tree holds special significance for the church. Parts of the walls to the nave are built from ancient split oak logs — some over one thousand years old making this the oldest wooden church in the world.

The most unusual kneeler (and definitely the most amusing I have come across) is the one of the king’s decapitated head and the levitating wolf crouched beside it. Levitation aside, this kneeler depicts a legend that is associated with the church and which is also depicted in carvings that adorn some of the beams supporting the roof. The story is of King Edmund and the faithful wolf, which you can read here.

Finally, the St Andrew’s Cross refers to the dedicated saint of the church: St Andrew, though I am not sure what the relevance of the fish and the seashells are as this church is far inland, miles away from the sea. Something for me to go away and research!

Do you have a parish church near you? Perhaps you worship there. If it has any kneelers I would love to hear about them and the stories that they tell.

Till next time

Hadden

https://parishkneelers.co.uk/appeal/

St Andrew is the patron saint of fishermen - he's one of the original 12 disciples and was a fisherman on Lake Galilee according to the account in Matthew (it's the 'come with me and I will make you fishers of men' bit)- hence the fish and shells.

An interesting piece. Thank you. When you say that "precious pieces of local art are being condemned to the processes of decay and degradation among heaps and heaps of modernity’s trash", it reminds me of a passage from a book I translated a while ago:

https://blog.oboluspress.com/p/witnesses-to-destruction

"Whatever regret or disgust we may feel, it is our right and duty as artists to struggle for these places and this society as our forefathers did for theirs — to preserve them in pictures, to honour their beauty, and to show how much we loved them."